What is Lymphosarcoma in Pets?

Lymphoma is also known as lymphosarcoma or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

It is one of the most commonly treated cancers in our practice. Many different species of animals can develop lymphoma, including humans, dogs, and cats. The disease can take on many forms. The most common form of lymphoma in dogs starts in the lymph nodes; usually first noted under the jaw. Other forms of lymphoma can start in the chest, abdomen, bone marrow, or other sites such as the skin. In cats, the most common form occurs in the abdomen, while the form that occurs in the peripheral lymph nodes is relatively uncommon. Some cats are concurrently positive for retroviruses (FeLV, FIV). However, a cat need not be FeLV or FIV positive to have this disease. An underlying viral cause has not been identified in dogs.

HOW IS LYMPHOMA DIAGNOSED?

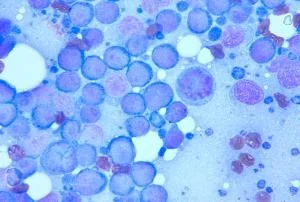

The means by which the disease is diagnosed depends on what form is present. For example, in patients with generalized lymph node enlargement, a fine needle aspirate (FNA) can often give us a preliminary diagnosis.

In cats with thymic lymphoma (a form arising from the chest) an ultrasound guided biopsy is usually necessary to make the diagnosis. Once a preliminary diagnosis is made, a definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy and/or polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The important differentiation between T-cell and B-cell lymphoma can be made with a biopsy and immunohistochemistry or with PCR from aspirates. The PCR, however, has a greater chance of a false negative result.

Cytology from a fine needle aspirate taken from a dog with lymphoma. Aspirates help the oncologist know what kind of cancer is present, but also allows staging, a measure of how aggressive a particular cancer is.

STAGING:

Because lymphoma can spread to almost any tissue in the body, a thorough work-up needs to be done to determine the stage of disease. This lets us know how advanced the lymphoma has become and ultimately helps us decide what treatment would be most beneficial. Tests recommended for staging include a complete blood count, serum chemistry panel, urinalysis, thoracic radiographs, abdominal ultrasound, and bone marrow analysis (in selected cases). These tests help give us an indication of the extent of your pet’s cancer and his/her general health and ability to undergo treatment.

What does “stage of disease” mean?

We designate a patient’s stage from I to V. Stage I disease means the cancer is confined to just one lymph node. Stage I is rarely diagnosed in pets. Stage II refers to cancer in more than one lymph node, but in only one region of the body. Stage III refers to cancer in the nodes throughout the body. Stage IV refers to disease in the nodes and spleen or liver. Stage V refers to all of the above plus cancer in the bone marrow, blood, or other sites not listed above. There is also a sub classification of A vs. B. A means the patient is not ill with the disease while B indicates clinical symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, fluid in the lungs, etc. Stage IIIA is usually the earliest we detect the disease in dogs. Even later stages of lymphoma are very treatable.

How is lymphoma treated?

Chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment for lymphoma. Chemotherapy means “chemical treatment” and refers to drug therapy. Anti-cancer drugs can be administered intravenously, subcutaneously, or even orally, depending on the drug chosen. Intravenous (IV) drugs are administered directly into a vein through a catheter. Special care must be taken when using anti-cancer drugs. These drugs can cause serious problems for your pet if administered inappropriately and can also cause problems for the administrator if not handled and disposed of properly. At ACIC we have a “Hazardous Drug Safety and Health Plan” that strictly follows Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards and involves training our nurses and doctors in proper preparation, administration, and disposal of these potentially hazardous drugs. You will be provided with written information regarding chemotherapy safety.

Strict adherence to chemotherapy safety and utilization of specialized safety equipment at ACIC is mandatory.

WILL MY PET GET ILL WITH TREATMENT?

Fortunately, animals tolerate cancer treatments far better than people. The incidence of serious side effects such as vomiting, diarrhea, or infection tends to be less than 5%. This is for several reasons, the most important being the dosage levels used. In people, dosages are much higher and therefore people suffer the side effects to a greater degree. In animals, our primary concern has to be quality of life, therefore we choose the maximum dosage possible to treat the cancer while not causing significant side effects. Potential side effects will be discussed in detail at the time of your consultation.

Will my pet lose hair?

In general, no. Certain breeds are at risk for hair loss (Poodles, Old English Sheepdogs) but the majority of breeds of dogs and cats do not experience hair loss with chemotherapy.

What is my pet’s prognosis?

While lymphoma is a very treatable disease, it is not a curable disease. Our goal with treatment is to put the cancer into remission, which means there is no detectable evidence of cancer on routine physical examination and testing (i.e. x-rays and ultrasound). We know, however,that every last cancer cell will not be killed, and eventually the disease will come back. If we are successful at obtaining a remission, your pet’s quality of life should be back to normal. It is important to understand that eventually the disease becomes resistant to treatments. The length of remission for lymphoma will depend on the type of lymphoma present and the extent of disease. In general, greater than 90% of dogs and greater than 75% of cats will achieve a complete remission with treatment. There are patients that are resistant to treatment from the beginning, but fortunately this is uncommon. The length of remission also depends on the chemotherapy protocol chosen. This will be discussed with pet owners on a case by case basis. For most types of lymphoma, the median survival for patients receiving no treatment is 30 days. With prednisone alone, median survival times noted are approximately 75-90 days. Median survival times reported for dogs treated with chemotherapy ranges from 8-14 months. You need to keep in mind that these are averages, therefore much longer survivals are possible as well as shorter survivals. When patients come out of remission, additional treatment courses are usually recommended.

Lower grade forms of lymphoma exist. Most notably, cats with small cell lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract are treated less aggressively (with only oral chemotherapy) and can enjoy many years of good quality of life. Extra-nodal forms of lymphoma (those occurring outside of the lymph node system, e.g. nasal lymphoma in cats) can often be treated either with surgery or radiation therapy and cures are possible.

A new lymphoma vaccine (specifically for use in B-cell lymphomas) is currently available. Studies are very preliminary but appear promising. The vaccine is started after the completion of the University of Wisconsin Canine Lymphoma Protocol. It is given once every 2 weeks for 4 treatments and then a booster vaccine is given every 6 months as long as patients are in remission. The vaccine appears safe and has not been associated with any significant side effects. However, the vaccine is currently expensive and can significantly increase the cost of treatment. The doctors at ACIC will discuss this with you and provide current financial estimates.